The first computer I spent time on was a IBM PCjr, acquired around fourth grade, 1984 or so.

Before that, I really had no idea what a computer was, or what one did, save perhaps my Big Trak, a tank-like toy with a microprocessor that could be “programmed” via buttons on its back to crawl forward or backward or spin or fire its “laser.”

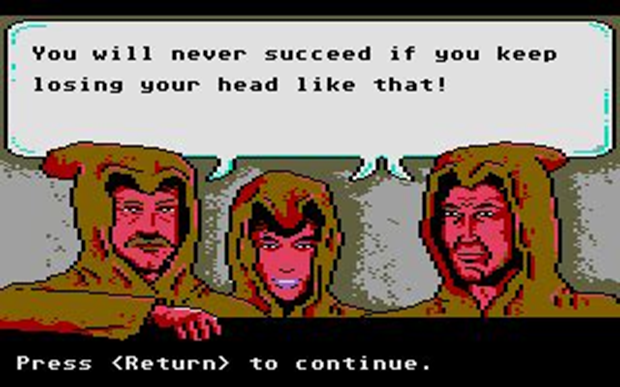

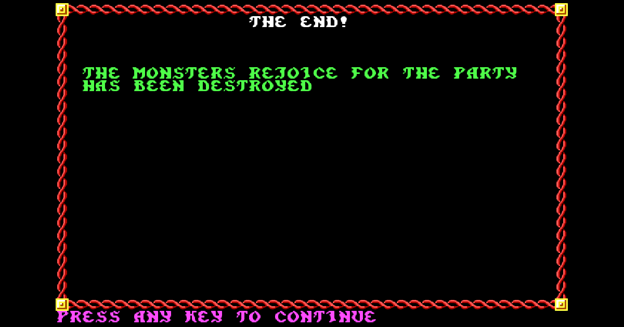

The aggressive PEW PEW PEW noise of a Big Trak is ironed directly onto my synapses even more keenly than “YOU MUST GATHER YOUR PARTY BEFORE VENTURING FORTH,” and that is saying a lot.

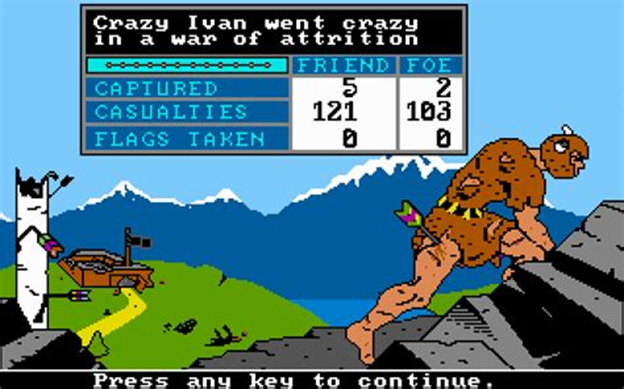

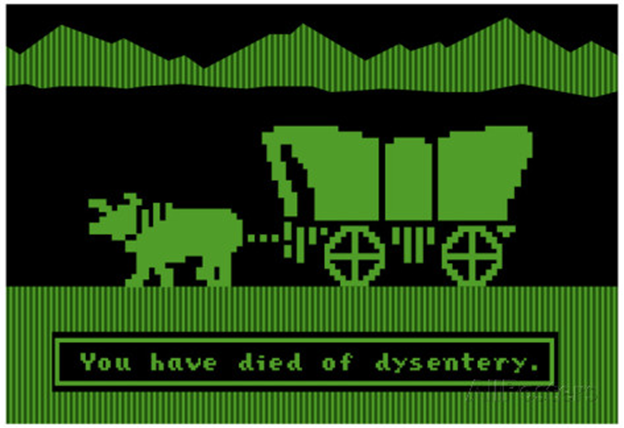

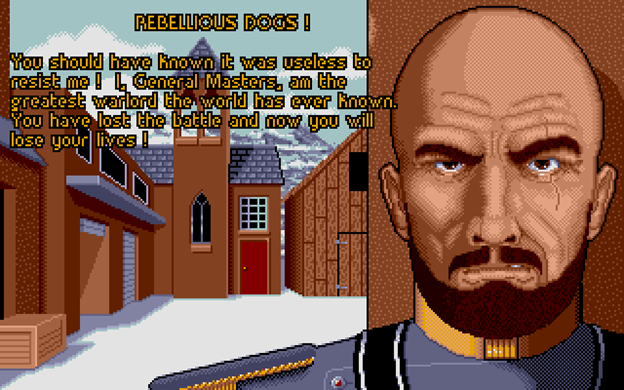

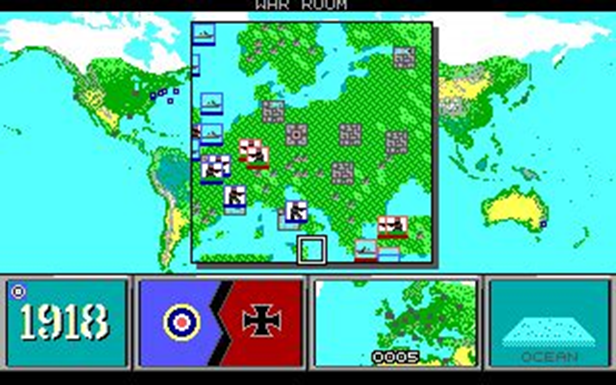

The PCjr was an absolute beast in computing terms, the 1984 equivalent of giving a 9-year-old boy a Ford Mustang and carte blanche. 16-color monitor, infrared keyboard, a clunky 5 1/4 disk drive, two mostly useless cartridge slots (I only ever had the BASIC cartridge), and 128k of RAM to power its trusty 8088 processor running at a lightning 4.77 mhz. I fed that monster many floppy disks as a young and ambitious high priest in charge of sacrificing 360k at a time to an increasingly demanding deity. I gamed, I learned DOS, I learned BASIC, and I also learned how to troubleshoot.

Years later the junior was replaced by a clone 8088 with 512k RAM and two disk drives, but its 4-color CGA monitor (the PCjr’s monitor was incompatible with anything else) was a sore point. Eventually I got a 16-color EGA upgrade, and later, an Adlib sound card, and a hard drive, which held an astounding 30 MB. The clone died at some point and was replaced with yet another 8088 clone, an XT “Turbo,” which via a red button could press its clock speed to a terrifying 8 mhz.

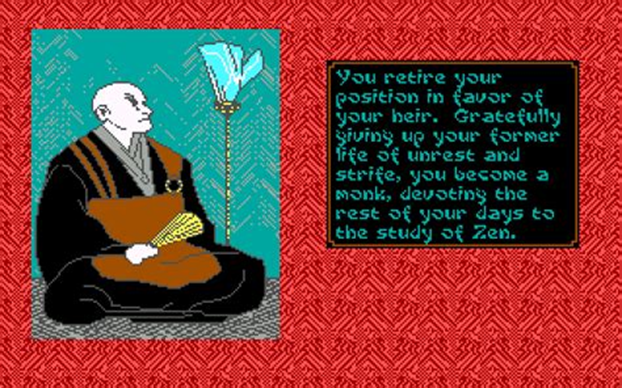

I still had the XT Turbo when I went to college, but in an misguided effort to reinvent myself as a long-haired, guitar-playing Luddite, I left it in a closet. I’d become convinced that all my years of computer gaming had left me socially stunted and I needed to keep off of screens.

This phase lasted several years and didn’t work well. I missed the 286s, the 386s, and even the 486s, and I had managed to become computer-phobic right as the internet took off. Eventually, however, a roommate gave me an email account on one of the university’s servers, and I used it in conjunction with the 24-hour terminal labs on campus to explore this newfangled web. I slowly became tech-savvy again.

By 1995 or so, it became clear that biking a mile to the nearest lab was impractical if I wanted to read something on the net, write a paper, roleplay, etc. The XT Turbo, which would have qualified as a Porsche in 1984, was now a Model T (I also skipped years of game console development after the Super Nintendo, requiring extensive supplemental recovery, but that’s another post).

So I saved up every cent I had from part-time work and bought a Pentium. 120 mhz (overclocked to 133), 28.8 baud modem, VGA monitor, CD-ROM (read only), and perhaps most strikingly, Windows 95.

I was on the information superhighway.

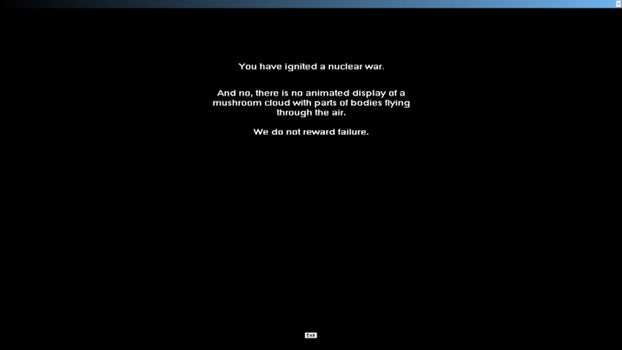

My grades plummeted immediately.

You can literally see on my undergraduate transcript exactly when I got this devil’s machinery. My rapid recovery in my four last semesters depended on strict internet rationing, partially aided by the purchase of a 56k baud modem that reduced the time spent twiddling my thumbs.

The Pentium went with me to Boston in 1999 upon graduation. It became clear, however, that I was outgunned. My first job in Beantown gave me a 333 mhz Celeron that they had lying around, and after I bought a car that summer, I bought a Pentium II in the fall. 400 mhz, and of course I added the stereotypical “necessary” Voodoo 3. By 2002, I had a Pentium IV running at a ridiculous 1 Ghz.

In 2003, I got my first laptop, a hand-me-down Pentium III, and after a stint as a laptop tech, I decided to start building from components. I built a massive full tower (I still have the case, which figures into this story later) that held a long succession of processors, with a reliable Q6600 being the longest-lived. I also acquired a X31 Thinkpad around 2007, a model I’d fallen for hard when doing warranty repair on them, and I wrote my dissertation on it. It was destroyed accidentally around 2010 (long story) and I could never quite find a good replacement for it until very recently, depending on several Dell workhorses from UHD, when I ditched my work machines and bought the modern version of the X-series, a Thinkpad Nano.

The advancement of what I consider a minimum has, umm, increased. Right now I’m writing this post on a water-cooled i7-11700k with 32 gigs of DDR4 and a RTX 3060 Ti driving two 4k monitors, which makes the 1984 PCjr look like something scrawled in the margins of a cave painting in France, and it’s a fairly mid-grade setup. In addition to the Nano, which I take to the office, I have a recent iPad that I use almost entirely for streaming and gaming, a PS5, and a heavily modified Steam Deck.

This is adequate.

I gave my full tower to my 8-year-old son, who now has unwitting custody of the trusty 1660 Ti upon which I rode through most of the pandemic. He also has access to a Switch, an 8-bit NES that I restored, and a battered internet-free iPad.

My younger son is too rough on tablets, but has an ancient, heavily armored iPhone, also locked down, the use of which is rationed carefully. But his creaky phone is far more powerful than the 1984 PCjr. With a peripheral exoskeleton, it could run rings around my first laptop.

My goal with him and his brother (something I’ve discussed here before) is not to replicate the same cool experiences I had, but to make sure they are comfortable around tech, they can solve most problems related to it by themselves, and their internet usage is never overwhelming nor addictive.

The tools for moderating such activity are far better now than they were for me; my only saving grace was that I didn’t get a modem until I was about 20. I am thankful that I had good early tech exposure, as it helps keep me happy and employed, but it’s quite possible to have too much of a good thing.

It has not escaped my notice that they are almost as enamored with the NES as they are with the Switch. The NES is not much more complicated than a toaster (it gets hot enough to make toast, to be sure) but it remains a mean gaming machine. They are also just as excited about mundane Lego sets as they are anything on a PC. The Big Trak is still cool, perhaps only a little less than the Arduino robot my older son and I built (easier to program, too). In some ways they have it better, as they have access to both the old and the new, and they can see the advantages and disadvantages of each. My job is to act as a mediator of taste.