Little has transpired lately that cheers me, so here, I have decided to praise something that I like.

I’ve been using Steam to buy PC games for over a decade. The best one in my alarmingly large collection is, by any measure, The Long Dark. It has been in Early Access since at least 2015, but it doesn’t matter. It is pretty much everything I might want in a PC game, but at the same time, it is maddeningly incomplete, illogical, and nonsensical. But this is a case where the flaws create the sublime.

The narrative version of the game, “Story Mode,” is fine, if still incomplete after seven years of development. Irrelevant, though. The core fan base of the game is in “Sandbox,” where you, as a recent plane crash survivor on a remote Canadian island after a ill-defined apocalypse, are tasked to survive as long as possible.

That’s it.

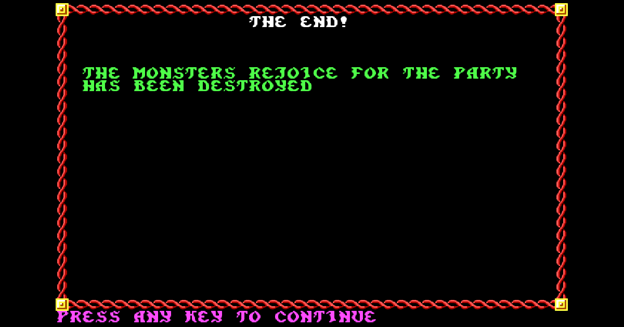

It’s very cold. There are no living humans save yourself. Much of the wildlife is hostile. The weather is fickle and deadly. Supplies are rare and randomly placed in every new game, and “safe” areas are widely spaced from each other, forcing dangerous treks. It’s a game of careful planning and preparation, and in the end, you’re going to make a mistake and die, as TLD is permadeath. You can stop playing to save your progress, but dying is permanent, and you must start over.

It is a gorgeous game. The weather is dynamic, moody, and a character unto itself. A typical game consists of long stretches of pleasant monotony, carefully building up a reasonable shelter, broken by abrupt moments of sheer terror during meticulously planned expeditions to distant corners of the island for rare supplies.

But the game is also highly unrealistic, and by design.

Crafting items is essential to survival, but many of the most painfully obvious items that a reasonable individual in such a circumstance might think to construct are not featured.

For example, I can build a fire, repair clothing, sharpen a tool, forge an arrowhead (if I’ve got a forge), even fashion a rabbit trap and build a self bow, among other useful survival tasks.

But I can’t make a spear, the most basic and easy to make Paleolithic weapon, even if items like knives, arrowheads, cured gut, and hardwood saplings are in the game.

I can’t fashion a sled to carry more gear or an animal I’ve just killed so I can harvest it in a safer location. They did eventually implement quartering, but it’s not that useful.

Even with a hatchet, I can’t manually cut down a tree – I’m limited to hacking branches that have already fallen to the ground.

I can’t fashion a stronger or larger backpack other than the one I have at the beginning. It’s possible to make a satchel out of a moose to supplement my carrying capacity, but I can only carry one.

I can’t build anything larger than a small snow shelter, despite, again, having multiple hatchets, knives, and various appropriate tools, or modify an existing structure in any way.

Several firearms exist in the game – a .303 carbine and a .357 revolver – but the stock character, despite apparent 20/20 vision, can barely hit a deer at 20 yards when he/she is standing still and the ungulate in question is standing still.

Finally, perhaps, raw meat spoils far too quickly, even if left outdoors to freeze , and there is no way to preserve/pickle anything long-term.

Oh, and don’t even get me on the lack of booze and candles.

Now, you’d think a reasonable individual like myself would laugh all the way to never playing the game again, after taking all of this nonsense into consideration.

But all of these examples are examples of good game design. Games are never supposed to be realistic. They’re supposed to be fun and challenging. Walking right up to reality and becoming indistinguishable from it is not the goal.

Spears would unbalance the game. Solo wolves and bears and even the odd moose would be too easy to fend off, and conserving and handloading ammunition for the guns would be less important.

A sled would make the “expedition for supplies” play cycle too easy, which encourages careful inventory management.

Forcing the player to harvest an animal where it falls introduces considerable strategy when hunting.

Allowing the player to deforest an area or improve shelters in an area also unbalances the carefully crafted maps that balance shelter, resources, and danger.

A realistically accurate rifle would make hunting trivial.

Yes, constructing a bear-proof log cabin, with an endless supply of firewood and months of cured meat, plus some pit traps that would allow me to hunt without wasting bullets… that would be ideal. But it would remove the sense of improvising every moment, of immediate danger and death around every corner.

These limitations can also be explained. The character is a unlucky bush pilot, not a mountain man/carpenter/hunter/craftsman. So the technology and abilities is closer to what an average Joe might be able to do while in a perpetual state of total panic.

In other words, nothing heroic.

The first time I encountered a bear in the game, I slowly backed away, despite being heavily armed and theoretically prepared. I only had one life. Having one life and holding on to that one life requires a different kind of thinking, decision-making, and risk calculation. The strange restrictions that I listed before, then, actually increase my sense of realism. Letting the player get too powerful and capable would turn it into every other poorly-balanced RPG in existence. The limits are what make it great.